I was somewhat lost, extremely confused, and kind of frustrated. I was 10,000 miles from California in a city called Mombasa on the South Coast of Kenya. I thought that I had proper instructions from my host to get to my Airbnb, but she posted directions from the train station (Mombasa Terminus), however, I was at MOI international airport. So, I had to figure out how to get to my apartment rental near Diani Beach and I didn’t like the $4,000 Kenyan Schillings price that Bolt (an international ride sharing app which is cheaper than Uber) was charging to get there. So, I decided to take a taxi about halfway there instead. This would put me back on track with the route that my host had given me. It would also require that I take the Likoni Ferry. This ferry ride would be an unexpectedly healing experience for me. It was profoundly spiritual and deeply fulfilling.

I’m aware that this must sound absurd to the average Kenyan. It must be the equivalent of someone saying they were moved to tears by the beauty of the people on the BART Train, or they had a cultural awakening on the back of an AC Transit Bus. We tend to not recognize the potency of what we see every day. Sometimes it takes looking at the world through the eyes of the tourist to see what we take for granted. My ride on the Likoni Ferry represented one of those super rare occasions when you recognize that you’re in a moment within the actual moment. I walked onto a boat with no less than 1,000 other Black people who brought bikes, had babies on their backs, and carried bags. I was no doubt the only “American” and probably the only tourist on the entire ferry. My Bolt driver advised me not to get on. I’m glad that I’m hardheaded and refused to take his advice.

I had an enormous suitcase that was 2 kilograms overweight at the airport, but the nice lady at Kenyan Airlines allowed me to slide without a penalty. I also had a huge burgundy backpack that I once used to go camping in Yosemite National Park for three days. It has several compartments, zippers, and hidden storage space. It’s great for backpacking, but it’s extremely conspicuous when it comes to city walking.

“It’s not safe for you to take the ferry with those bags,” he said.

“Really?” I replied somewhat sarcastically.

My driver was a very long limbed but somehow average sized man named Peter. It took a few phone calls and me having chase him down in the Airport parking lot for him to see me when he arrived. This turned out to be a bonding experience for us. By the time I sat down in the backseat of his Hyundai I felt like we were homies.

“Yeah.” He said sharply. “Anybody can go through your bag on the ferry. Be careful.”

Every African that I have ever met in Africa thinks Africa is the most dangerous place in the world. When I tell them that major American cities are way worse in terms of theft and violence they refuse to believe me. I once tried to explain this to a Liberian woman in Accra, Ghana. She shook her head then told me with a strong conviction; “No, America is heaven.” Of course I didn’t tell Peter any of this. I just said:

“Ok, I’ll be careful.”

I actually appreciated his advice. It was just that my lack of speaking Swahili—the official language of Kenya— prevented me from explaining my perspective. I live my life knowing that I can be robbed, maimed, or killed any second. I’m always vigilant when I’m in public spaces and there was nothing that he could say to make me any more or any less aware of my surroundings. There was also nothing he could tell me to keep me from getting on that ferry. In fact, the more he spoke the more excited I got about boarding.

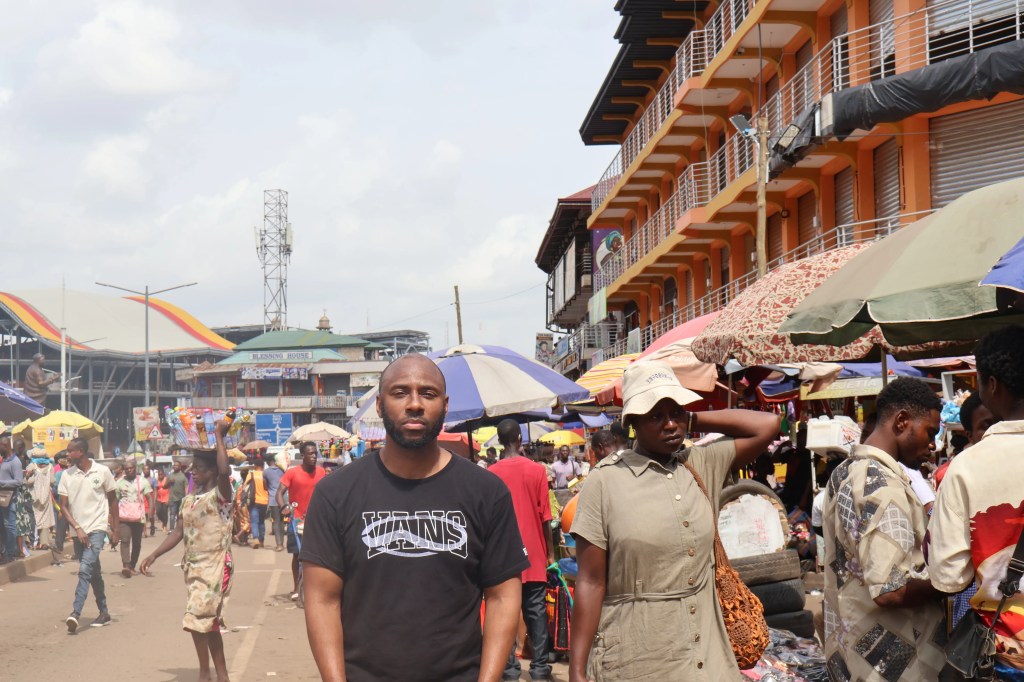

I was sick of being separated from normal Kenyan experiences because I was a visitor from a foreign country. The tourism industry is structured like a traveler’s ghetto in that the local government keeps you boxed in so they can control the outcome of your experience. The roads that you can walk down, the restaurants where you can eat, the people you encounter, and the way you commute is all predetermined. In the ghetto the ultimate objective is to keep you trapped at the bottom of society. In tourism the sole purpose is to manipulate your mind by giving you a watered-down version of culture while encouraging you to spend way more money than you should on items that you do not need. This stimulates the local economy and makes the billionaire hotel owners even more wealthy.

Think all-inclusive resorts. They keep you fenced in for most of the day. They give you a swimming pool, beach access, or both. They give you a menu with a few native foods and local juices alongside hamburgers, chicken strips, French fries and Coca Cola. They employ locals to serve you and perform for you. And they only allow you to move about the city in chartered vehicles that the hotels own. All of this while people live in squalor right outside the gates of your paid fantasy. Nah, I ain’t with it. I have never been with it. I was going to hop on that ferry with the people of Mombasa and I was ready to deal with whatever consequences came with it.

We had to get out of the car about 200 meters from the ferry station. Cars and tuk tuks are allowed on the ferry but the passengers must pay. Pedestrians and cyclists are free which was another major incentive for me to take the ride. Peter insisted on walking me to the security check-in. After I paid Peter, I was heading to the embarking point when three Kenyan security guards stopped me.

“Jambo! Jambo! You come here.”

I walked over to the men pulling my oversized suitcase behind me.

“What is in the bag?”

“My clothes. Most of them are dirty.”

“Open the bag.”

I opened my suitcase, and the main guard who was asking all the questions sifted through my belongings while noticeably avoiding touching my dirty drawers.

“Where are you from?”

“I’m from California.”

“Oh, USA. Do you bring a gun?”

“No, I left all my guns at home.”

We both laughed, then he zipped up my suitcase and let me go. I walked into a large rectangular area with benches that were being quickly filled up. People had bags full of fish, beans, and clothes to sale on the other side of Kilindini Harbor. A woman walked by while gracefully balancing a large green sack on her head. A teenaged boy pulled up on his bike. A mother and father sat down with their two boys. The males in that family had clearly come straight from the barbershop because their lineups were immaculate. The people kept arriving. Each and every one of them had business to attend to on the other side. All of them moved with the familiar mundanity of a morning commute as it was about 9:30am.

I’m certain that they saw diversity in one another. I’m sure they could determine tribal affiliations by body type, gait, or skin tone. They could probably tell who was from the countryside and who was from the city based on accent and attire. Perhaps they could decipher who was formerly educated versus who had been working on a family farm their entire lives. I could not figure out any of these things, nor did I try to. All I saw was Black people and all I heard was the intermittent sounds of a soothing African tongue that I did not know how to speak. I was calmed by not being able to understand sentiments that might ruin my day. I was unaware of who was gossiping, who was cursing, who was being offensive, or who had a different political ideology than I do. I was blanketed by my obliviousness. I was comforted by what I did not know. Then we began our descent.

It was time to be loaded onto the ship which was at the bottom of a cement hill. I walked in synchronicity with the people of Mombasa. I was in the middle of the crowd, in a country in Africa, headed into the bottom of a boat. I thought about the middle passage—the indescribably brutal tragedy that ripped my ancestors from the continent and forced them into chattel slavery for centuries—but this was not a kidnapping. This was a reconnection. This was an initiation ritual. This was a baptism into a culture that had the power to redirect my spirit. I was being reunited with everything that had been lost. I pulled my luggage behind me onto the vessel, and I carried my backpack like a thousand burdens on my back. I did not stop walking. I did not speak at all. Even when asked a question in Swahili I just shook my head, no. I did not want to speak English. I did not want to be an American. I did not want to be an individual. I wanted to be at peace. I wanted to be whole and move within a body of people striving toward a singular destination. As I found my position on the ship, I looked up to my left and saw black people going up the stairs to the next level. I was surrounded by the Kenyan people—my people, whether they knew it or not. And as the powerful motor of that ferry propelled the entire lot of us across the water, I knew that I belonged. And I knew that I was safe because everyone was far too preoccupied with their own bags to be concerned about taking mine